It’s raining outside as I write this but I would love to be out there running right now. These days I rarely need to motivate myself to lace up my trainers, but for many years it wasn’t like that. So I’m going to tell you a story about running, but it’s not really about running. Instead I want to illustrate what I’ve learned about motivation and how to tap into it. You might hate running – and I’m really not aiming to convert you – but running is how I learn a lot of my life lessons. The secrets of endurance running certainly helped me get through the LockDown.

Over time the reasons I run have changed

When I started running in my 30s it was because I saw it as a way to lose weight. I’d been relatively fit before having kids but gained weight with both pregnancies. I’d run a few times a week to try and get back into my favourite jeans.

I entered a few 10km races to encourage myself to train more consistently. Without a race to aim for I’d not get around to training. This motivational technique is called ‘accountability’ – holding yourself to account by committing to things (or people). It wasn’t easy to fit running in at that stage in my life, there’s always a lot to do when you have small kids – and you don’t have a lot of spare energy. I didn’t really enjoy running much at this time, I had been a decent runner as a kid and plodding round slowly wasn’t great for my self-esteem. But when I entered a race, I usually managed to go out and run a bit more.

Carrot and stick

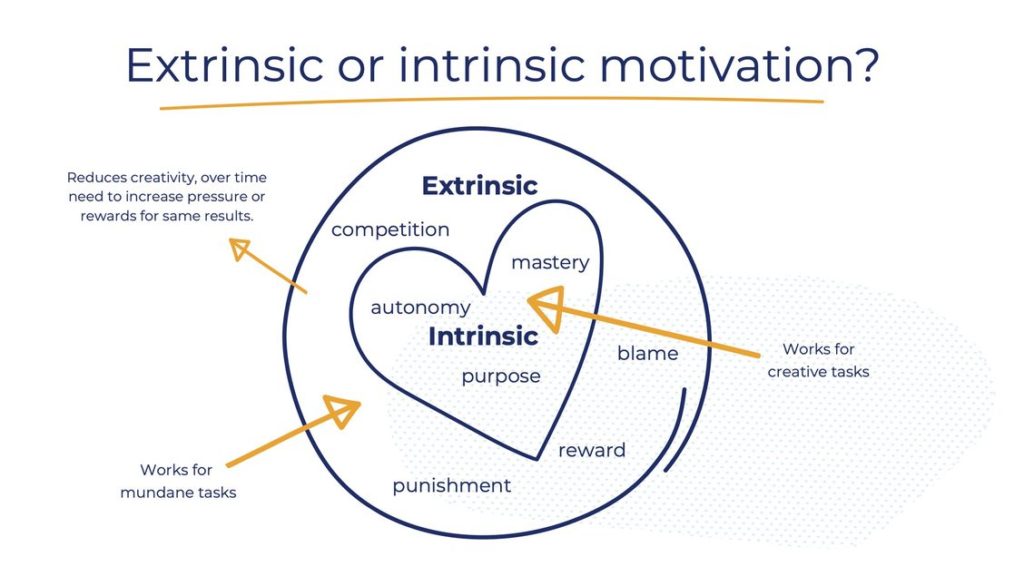

This is classic ‘extrinsic’ motivation – also known as the ‘carrot and stick’ approach. We encourage ourselves and others via rewards and threats. You tell yourself ‘if you don’t run you’ll be fat, if you keep running you’ll get back into your jeans’. It rarely gets the best out of us – and we rarely enjoy the process. If you hate running, it might be because you’ve done it for extrinsic reasons (get fit, lose weight, because you feel you ‘ought to’).

Research shows extrinsic motivation can be damaging to performance at work. It can reduce creativity and the levels of threat or reward needed to keep producing the same results have to increase over time to produce the same results. But in the short-term in can help with unpleasant tasks we don’t much want to do – like running!

I accidentally discovered the limitations of extrinsic motivation when I once bribed my kids to wash my bike for me. They were about 5-6 years old at the time, and offering them 50p for the job that seems like a good deal to me. It worked like a dream the first time and I thought I’d cracked parenting (and keeping my bike clean). But next time I asked them to clean my bike the youngest just shrugged and demanded £2.

Tapping into intrinsic motivation

So if carrot and stick is a bad idea, what works better? Research tells us the trick is to find a way to satisfy your inner motivators: mastery, purpose and autonomy. I didn’t realise it at the time but I was about to tap into mastery and purpose in my running.

I’d always wanted to do a marathon. So I decided to set myself a bigger challenge and enter a half marathon (a sense of purpose). I also set myself the target of doing it in less than 2 hours: a respectable target for a woman in my age group (ie slightly past it, athletically speaking). And I was chuffed with myself when I crossed the line in 1:56 – I felt I had done well (that’s mastery kicking in). A year later, I stepped up to train for my first marathon. I had wanted to run a marathon this since being inspired by Ingrid Kristiansen in the 80s (purpose again). Even the training felt exciting – each week the ‘long run’ in my training schedule became longer than I had every run before. Every week I was pushing myself – it was the first time I’d run 14 miles, 15 miles, 18 miles… each week felt like a new achievement (that’s mastery fuelling me, although at the time it was mainly tea and Haribo Starmix).

Again I set myself a target time – I wanted to complete in sub 4 hrs, which is considered a respectable marathon time for a beginner at my age. Paris was a good choice – a glamourous route around a city I love – that helped too (purpose – ‘any excuse to go to Paris’ I thought).

Carrots aren’t always bad for you

I crossed the line in 3:56, delighted. I had achieved my goal and work and family commitments meant I didn’t run regularly after that for a few years until I met two new friends who had just entered the York Marathon. I joined them for some of their training runs. But cheering Julie and Miyako on race day I wished I was racing not stood on the sidelines. My extrinsic motivation had been re-activated. I thought I could improve on my PB (mastery). This drive to improve saw me running at least two marathons a year for the next few years. Each time the desire to achieve a faster time helped me finds the will to make space in a very busy working-mum diary to fit in 4-5 runs a week of up to 20 miles.

Extrinsic motivation has limitations but isn’t all bad – there were times when that competitive edge drove me to dig in and perform better. One time I had set off a too fast in a race and suddenly I hit the infamous ‘wall’ around 22 miles. I went from striding easily with confidence to slowing suddenly, feeling like my legs were made of a strange combination of jelly and concrete. I reached my lowest point around mile 24 when a runner in a Bat Man costume overtook me and something snapped (pride, I think) so I dug in to beat the caped-crusader, also managing to set a new PB and qualify for London and Boston marathons.

Running for the joy of it

As a runner there comes a point when you stop getting faster, especially if you start running in your late 30s. So how do you keep running when you aren’t getting better any more and so mastery can no longer motivate you?

A few years ago my appetite for yet another gruelling 16-week marathon training schedule, where success or failure on race day rested on fine-tuning my pace by a few seconds here or there, started to wane. And few road race courses are as inspiring as Paris. Slogging around ring roads of cities and towns in huge groups; queuing for loos at the start – none of this appealed any more. So I got more and more into smaller races and off-road running. After doing a few 10km and 15km trail races I entered my first trail Ultra – a 55km loop around the Lakes. I’ve since gone on to do a 50 mile mountain race and run the 191 mile Coast-to-Coast route.

Increasingly running has become about the places I go and the people I run with – both for training runs and events. When my husband enters a big race in the alps I go along for 3-day training runs in those magnificent hills to help him prepare (purpose). And I have had many weekends away racing in the Lakes over the last few pre CV19 years with my friends. Instead of being about the races, running has become just the medium for getting into the hills with my mates, enjoying fresh air, visiting new and amazing places. My purpose and motivation has shifted – although I’m wise enough now to tap into that extrinsic motivation when I need to get up a big hill!

Making the most of motivation

Looking back on my relationship with running I can clearly see how intrinsic and extrinsic motivation has helped me, and deserted me, at times.

Understanding what can motivate us can be incredibly helpful at work, and in life. Many clients I’m working with as a coach will find themselves puzzled as to why they seem to have ‘lost’ their motivation. Managers of teams and organisations often wonder how they can motivate others better, or puzzle at why those around them are less enthusiastic or committed than them. Assessing those intrinsic motivation factors usually quickly helps us pinpoint the problem and generate ideas about how to fix it.

There are two lessons for me around motivation and how we can use it:

1. When possible, tap into intrinsic motivation: mastery, purpose and autonomy

Intrinsic motivation is like Green energy. It’s renewable and it doesn’t cause bad side effects. So wherever possible, stick to intrinsic motivation.

If you’re feeling less than excited about something you need to do simply ask yourself which of these ‘ingredients’ is missing and what options you have to increase them:

Autonomy – what would offer you more freedom around how you do this? What can you control? What are you assuming about how it needs to be done? Do you really have to do this?

Mastery – where is the opportunity for growth, learning or development? Might this task help you secure your next job or contract? Is there something you could usefully learn from this project that might be helpful for another area of your work?

Purpose – what could you achieve through this that would have meaning for you? What would it take for you to feel successful?

The same technique applies to those you are working with. If they are less excited about something than you, put yourself in their shoes and ask yourself how could I offer them more opportunities for autonomy, mastery or purpose? What might I be doing that gets in the way – am I being too controlling or prescriptive? Am I asking them to do something without explaining why or something they don’t think is useful? Am I expecting people to work in a way that doesn’t offer a chance to do things well and develop? Or better still, have that conversation with them directly.

2. Use the carrot and stick sparingly

There will always be times when we need that extra nudge to want to do something hard, boring or repetitive – and that’s when extrinsic motivation can be useful.

I often plan my longest, hardest training runs to finish where I can refuel with a hearty brunch or, better still, fish and chips. In a work context, sometimes it can be as simple as doing the tough task first in the morning, so you can then ‘enjoy’ the rest of your day. Or give yourself an incentive – once I get these invoices done I can have a cup of tea.

Habits are another way of motivating ourselves to do things we know we ought to (but find ourselves reluctant to do). The more we can ensure helpful behaviours become habitual, the more likely we are to stick to them.

We all have days when we feel more motivated than others, and parts of what we do that we enjoy more than others. Extrinsic motivation can help with those ‘necessary evils’ in life and at work, but we’ll get more done when we discover our intrinsic energy. Understanding motivation so we can spot what’s missing, decide what type of motivation to tap into and generate some ideas about how to grow our intrinsic motivators can help us get the best from ourselves, and other people around us.

Want to master your motivation? Get in touch for a chat about how coaching might help.